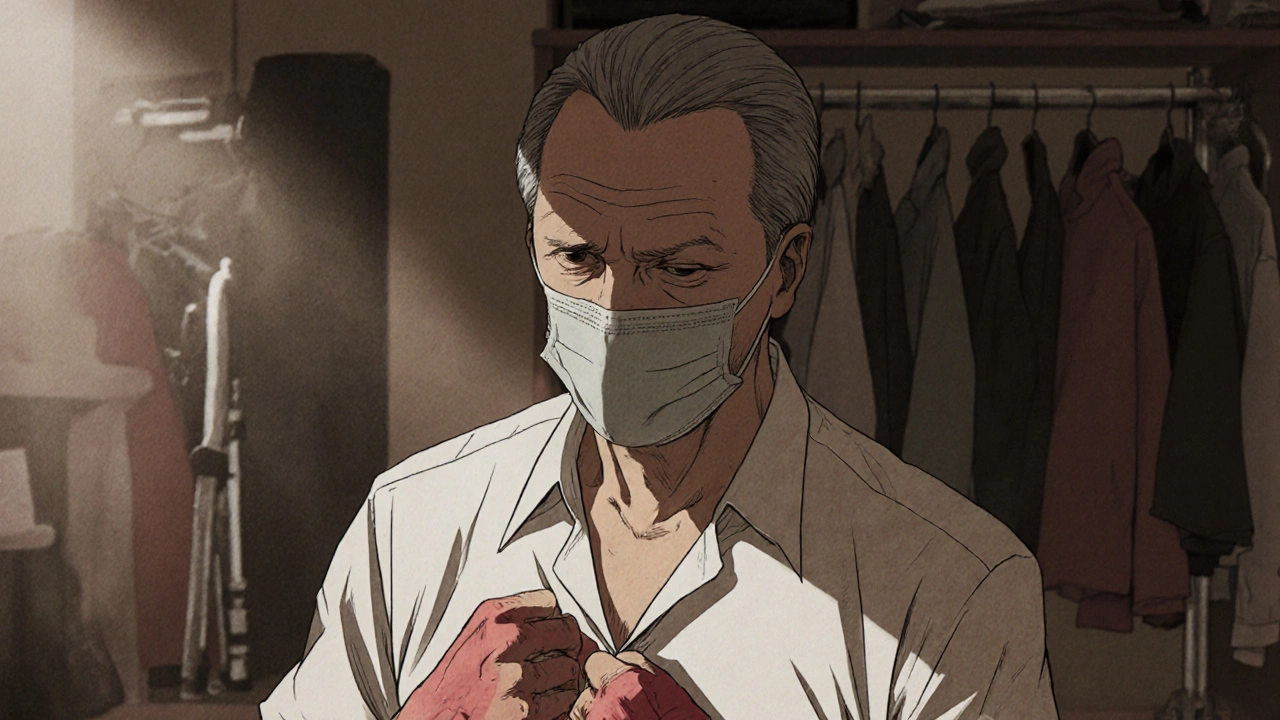

Living with Parkinson’s disease means learning to navigate a body that no longer moves the way it used to. It’s not just about shaking hands. It’s about taking five minutes to button a shirt, forgetting how to turn over in bed, or realizing your voice has faded to a whisper. For more than Parkinson’s disease affects 1 million people in the U.S. alone, and while it’s most common after 60, nearly 1 in 25 cases start before 50. The disease doesn’t hit everyone the same way, but one thing is always true: bradykinesia - slow movement - is the one symptom you can’t escape.

What Are the Core Motor Symptoms?

Doctors don’t diagnose Parkinson’s with a blood test or scan. They watch how you move. The diagnosis hinges on four key signs, called the cardinal motor symptoms. You don’t need all of them, but you need at least two - and one of them must be bradykinesia.

The first is resting tremor. It’s often called a ‘pill-rolling’ tremor because it looks like you’re rolling a pill between your thumb and finger. It shows up when your hand is relaxed, not when you’re using it. About 70% of people notice it first in one hand, foot, or leg. But here’s the catch: 20 to 30% of people with Parkinson’s never get this tremor at all. So if you don’t shake, it doesn’t mean you don’t have it.

The second is rigidity. Your muscles feel stiff, like they’re stuck in mud. Some people feel a ratchet-like resistance - called cogwheel rigidity - when someone moves their arm. Others feel a constant, smooth tightness, known as lead-pipe rigidity. About 85% of patients experience the ratchet effect. This stiffness isn’t just annoying; it makes turning in bed, standing up, or even smiling hard.

Bradykinesia is the silent killer of independence. It means your movements get slower, smaller, and fewer. Your face loses expression - people say you look ‘masked.’ You blink less. Your handwriting shrinks into tiny, cramped letters - a sign called micrographia. Buttoning a shirt can take three times longer than it used to. Walking becomes a shuffle. Arm swing disappears. And simple tasks? They turn into marathons. This isn’t laziness. It’s your brain struggling to send the signal to move.

The last cardinal symptom is postural instability. This comes later, usually after five to ten years. It’s not just being unsteady - it’s falling without warning. You might lean too far forward, lose your balance turning around, or trip over nothing. About 68% of people with Parkinson’s fall at least once a year. One in three falls repeatedly. Falls lead to fractures, hospital stays, and loss of independence.

Other Motor Signs You Might Not Notice

There’s more than the big four. Many people don’t realize these are part of Parkinson’s until they’re told.

- Dystonia: Muscle spasms that twist your foot inward or curl your fingers. It’s common in younger-onset cases.

- Stooped posture: You’re not just slouching - your spine curves forward, shoulders hunch. It affects 65 to 80% of people.

- Speech changes: Your voice gets softer, muffled, or monotone. On average, volume drops by 5 to 10 decibels - enough to make conversations in a restaurant impossible.

- Drooling: You’re not salivating more. You’re swallowing less. About half to 80% of people deal with this because the swallowing reflex slows down.

- Dysphagia: Trouble swallowing food or liquids. It’s rare early on but hits 80% in advanced stages. That’s why aspiration pneumonia - when food goes into the lungs - is the leading cause of death in Parkinson’s.

And then there’s akathisia - the inner restlessness that makes you want to pace, even when you’re exhausted. It’s not anxiety. It’s your brain stuck in overdrive.

Medications: The Lifeline and the Trade-Off

There’s no cure. But there are medications that help - for a while.

Levodopa is the gold standard. It’s the molecule your brain needs to make dopamine. Taken with carbidopa to stop it from breaking down too early, it turns into dopamine in the brain. About 70 to 80% of people feel dramatic improvement in their tremors, stiffness, and slowness. For many, it’s life-changing.

But here’s the catch: after five years, up to half of people start having motor fluctuations. Some days, the medicine works perfectly. Other days, it fades too fast - the ‘off’ periods. And then there’s dyskinesia: involuntary, writhing movements that happen when the drug peaks. It’s like trading one problem for another.

That’s why younger patients often start with dopamine agonists - drugs like pramipexole or ropinirole. They mimic dopamine without turning into it. They’re less likely to cause dyskinesia early on. But they can cause dizziness, sleepiness, and even impulse control issues - like gambling or overeating. About 50 to 60% of people get symptom relief, but side effects can be tough.

After 10 years, about 30% of people become candidates for deep brain stimulation (DBS). It’s surgery. Electrodes are placed in the brain to send electrical pulses that calm overactive signals. It doesn’t stop the disease, but it can reduce tremors, stiffness, and ‘off’ time by up to 50%. It’s not for everyone - it requires careful screening - but for the right person, it restores years of lost function.

Daily Living: The Real Battle

Medications help your body move. But daily living? That’s where you fight to stay independent.

Getting dressed becomes a project. Shoes with Velcro replace laces. Button-up shirts give way to pullovers. A 2023 study found that dressing takes 2.3 times longer. Buttoning a shirt? Three times longer. That’s not just inconvenience - it’s loss of dignity.

Walking isn’t just slow - it’s risky. Step length drops by 25 to 35%. Walking speed slows by 30 to 40%. You don’t lift your feet. You drag them. Your arms don’t swing. Your balance system is confused. That’s why physical therapy isn’t optional - it’s essential. Twelve weeks of targeted exercises can improve walking speed by 15 to 20% and cut fall risk by 30%.

Speech therapy helps. You learn to speak louder, take bigger breaths, and slow down. Occupational therapists teach you how to modify your kitchen, bathroom, and bedroom so you don’t need help. Speech changes aren’t just about being heard - they’re about staying connected. If you can’t talk to your grandkids, you start to withdraw.

And then there’s sleep. Dystonia at night. Restless legs. REM sleep behavior disorder - where you act out your dreams, sometimes violently. Sleep isn’t restful. It’s fragmented. And tired brains move even slower.

Sexual dysfunction affects 50 to 80% of men. It’s not just about desire - it’s about nerve damage, medications, and depression. It’s rarely talked about, but it’s real. And it’s treatable.

What Doesn’t Work - And What Might

No medication has been proven to slow or stop Parkinson’s. Not yet. Research is looking at drugs that target alpha-synuclein - the sticky protein that builds up in the brain - but so far, nothing has passed large trials.

Exercise, though, is the closest thing we have to a disease-modifying treatment. Walking, cycling, dancing, boxing - even tai chi - all help. The movement itself seems to protect brain cells. People who stay active longer keep their balance, their speech, and their independence.

And diet? It’s not magic. But protein can interfere with levodopa absorption. So timing meals matters. Eating protein at dinner instead of lunch can make your morning dose work better. Staying hydrated helps with swallowing and constipation - another common issue.

Progression: It’s Not a Straight Line

Parkinson’s doesn’t follow a clock. Some people stay stable for years. Others decline faster. The Hoehn and Yahr scale breaks it into five stages:

- Stage 1: Symptoms on one side only - mild, often ignored.

- Stage 2: Symptoms on both sides - still independent, but slower.

- Stage 3: Balance issues appear. Falls start. Still lives alone.

- Stage 4: Needs help with daily tasks. Can’t live alone.

- Stage 5: Wheelchair-bound or bedridden. Requires full-time care.

Most people reach stage 3 in 5 to 7 years. Stage 5? That can take 15 to 20 years - or longer. With good care, many live decades after diagnosis.

Final Thought: It’s Not Just About Movement

Parkinson’s is often called a movement disorder. But what really matters isn’t how well you walk. It’s whether you can still laugh with your grandchild. Whether you can hold your partner’s hand. Whether you can make coffee without help.

The goal isn’t to cure it. It’s to keep you living - as fully as possible - for as long as possible. That means medication. It means therapy. It means adapting your home. It means talking about the hard things - swallowing, sex, sleep, sadness.

You’re not just managing a disease. You’re rewriting your life. And that takes more than pills. It takes courage, support, and the stubborn refusal to let Parkinson’s define you.

Can Parkinson’s be diagnosed with a scan or blood test?

No. There’s no blood test or scan that confirms Parkinson’s. Diagnosis is based on clinical observation - specifically, the presence of bradykinesia plus either tremor or rigidity. Neurologists look for other signs like reduced arm swing, small handwriting, and a masked face. A positive response to levodopa also supports the diagnosis. Imaging like MRI or DaTscan may be used to rule out other conditions, but they can’t confirm Parkinson’s on their own.

Why does levodopa stop working over time?

Levodopa doesn’t stop working - your brain’s ability to store and release dopamine does. As Parkinson’s progresses, fewer dopamine-producing cells remain. These cells normally act like a buffer, releasing dopamine steadily. When they’re gone, levodopa hits the brain in spikes. That leads to ‘on-off’ fluctuations and dyskinesias - sudden, uncontrolled movements. This is why doctors delay levodopa in younger patients and use dopamine agonists first.

Is deep brain stimulation a cure?

No. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) doesn’t stop Parkinson’s from progressing. It doesn’t fix non-motor symptoms like depression, constipation, or memory issues. But it can dramatically reduce tremors, stiffness, and the ‘off’ periods caused by medication fluctuations. It’s most effective for people who still respond well to levodopa but have unpredictable side effects. DBS is surgery - it carries risks - but for the right candidate, it can restore years of independence.

Can exercise really slow down Parkinson’s progression?

Evidence suggests it can. While no drug has been proven to slow the disease, multiple studies show that regular, intense exercise - like brisk walking, cycling, boxing, or dancing - improves mobility, balance, and mood. People who exercise regularly fall less, walk faster, and maintain independence longer. The brain responds to movement by releasing protective chemicals and strengthening neural connections. It’s not a cure, but it’s the most powerful tool you have outside of medication.

Why do people with Parkinson’s drool?

It’s not because they produce more saliva. It’s because they swallow less often. Parkinson’s slows down the automatic reflexes that control swallowing. So saliva builds up in the mouth. This affects 50 to 80% of people, especially as the disease advances. Speech and swallowing therapy can help train the muscles. Sometimes, medications or Botox injections into the salivary glands are used to reduce excess saliva.

Is Parkinson’s hereditary?

Most cases - about 90% - are not inherited. But in about 10 to 15% of cases, especially with early onset (before 50), there’s a genetic link. Mutations in genes like LRRK2, GBA, and SNCA can increase risk. Having a parent with Parkinson’s slightly raises your chance, but it doesn’t mean you’ll get it. Genetic testing is rarely recommended unless there’s a strong family history and early onset.

What’s the biggest threat to life with Parkinson’s?

It’s not the disease itself - it’s complications. The leading cause of death is aspiration pneumonia, which happens when food or saliva enters the lungs because swallowing has weakened. This affects up to 80% of people in advanced stages. Falls leading to fractures and infections are another major risk. Managing swallowing issues with diet changes, therapy, and sometimes feeding tubes can reduce this risk significantly.

tushar makwana

November 30, 2025 AT 18:21Mary Kate Powers

December 2, 2025 AT 17:14Matthew Higgins

December 2, 2025 AT 23:02Tina Dinh

December 4, 2025 AT 11:03Richard Thomas

December 5, 2025 AT 17:13Sara Shumaker

December 6, 2025 AT 17:45Peter Lubem Ause

December 6, 2025 AT 19:56linda wood

December 8, 2025 AT 07:05Scott Collard

December 8, 2025 AT 22:14Steven Howell

December 10, 2025 AT 11:40LINDA PUSPITASARI

December 11, 2025 AT 17:23Subhash Singh

December 13, 2025 AT 11:53Andrew Keh

December 14, 2025 AT 13:47Robert Bashaw

December 15, 2025 AT 19:54