When your liver fails, there’s no backup. No reset button. No pill that can fix it. For thousands of people each year, liver transplantation is the only real chance to survive. It’s not a simple operation. It’s not a quick fix. But for many, it’s the difference between a slow decline and a second chance at life.

Who Gets a Liver Transplant?

Not everyone with liver disease qualifies. The decision isn’t just about how sick you are-it’s about whether you can survive the surgery and stick with the lifelong care that follows. Doctors use a scoring system called MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) to rank urgency. Scores range from 6 to 40. A MELD of 15 means you’re seriously ill. A MELD of 35 means you’re in critical condition and likely to die within months without a transplant.But high MELD alone isn’t enough. You must be free of active drug or alcohol use. For those with alcohol-related liver disease, most centers require at least six months of sobriety. That rule is controversial. Some studies show patients who quit for just three months have nearly the same survival rates as those who waited six. Still, centers stick to the six-month standard because compliance after transplant is everything.

Other deal-breakers? Metastatic cancer, serious heart or lung disease, or an inability to follow medical advice. Mental health matters too. If you don’t have stable housing, a support system, or the ability to manage daily medications, you won’t be approved. This isn’t about being judged-it’s about survival. Transplant centers have teams of social workers, psychiatrists, and addiction specialists who evaluate whether you can handle the demands of post-transplant life.

For liver cancer patients, the rules are even tighter. You must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm, or up to three tumors under 3 cm each, with no spread to blood vessels. If your tumor is bigger or your alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood marker is above 1,000 and doesn’t drop after treatment, you’re typically not eligible unless you get special approval.

The Surgery: What Happens During a Liver Transplant?

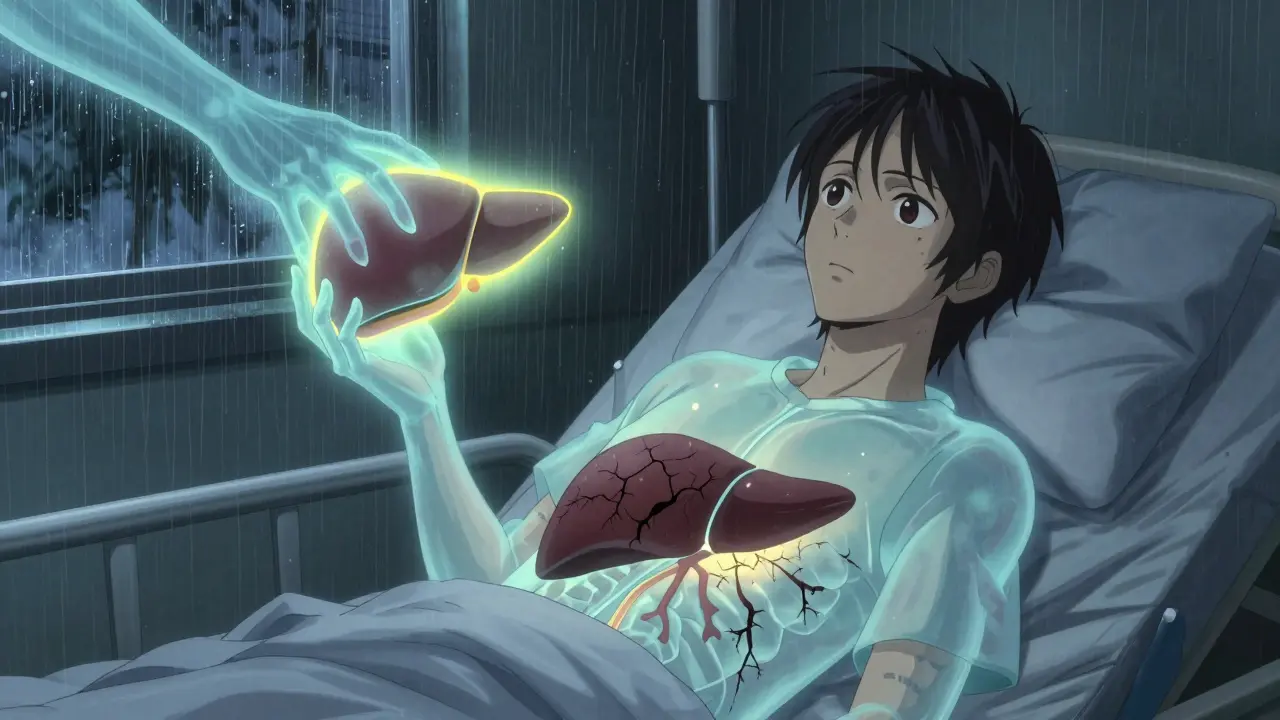

A liver transplant takes between six and twelve hours. The surgeon removes your damaged liver and replaces it with a healthy one from a donor. Most transplants use a donor liver from someone who has died (deceased donor). But some people get a piece of a liver from a living donor-usually a family member or close friend.Living donor transplants are faster. While you wait for a deceased donor liver, you might spend a year or more on the list. With a living donor, you can have surgery within months. But it’s not risk-free for the donor. About 1 in 5 donors has complications like bile leaks or infections. The risk of death is small-around 0.2%-but it’s real.

For adult recipients, surgeons usually remove the right lobe of the donor’s liver, which is about 60% of the organ. The liver regrows in both donor and recipient. Donors typically return to normal activities in six to eight weeks.

The surgery itself has three stages. First, the diseased liver is removed (hepatectomy). Then comes the anhepatic phase-your body has no liver. This is the most dangerous part. Blood pressure drops, and your body struggles to manage toxins and clotting. Finally, the new liver is stitched in. Surgeons now mostly use the “piggyback” technique, which leaves the large vein (inferior vena cava) intact, making the surgery safer and faster.

After surgery, you’ll spend five to seven days in intensive care. Total hospital stay is usually two weeks, but complications can stretch it to a month or more.

Immunosuppression: The Lifelong Trade-Off

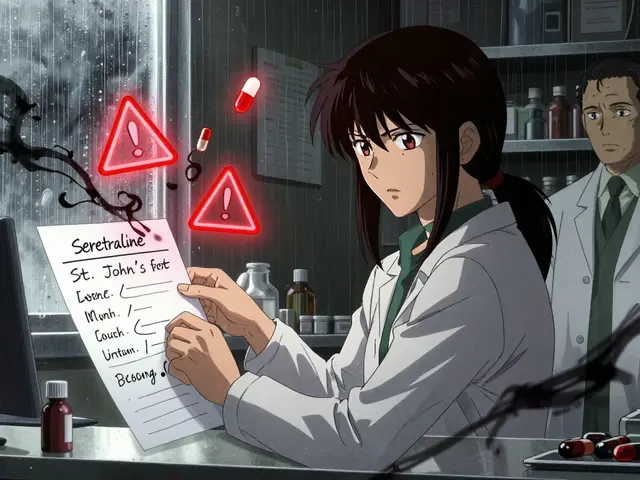

Your body sees the new liver as an invader. Without drugs to suppress your immune system, it will attack and destroy the transplant. That’s why immunosuppression isn’t optional-it’s essential.Right after surgery, you’ll get induction therapy. Low-risk patients get basiliximab, two IV doses on days 0 and 4. High-risk patients get anti-thymocyte globulin, given daily for five days. Then comes the long-term maintenance: a triple drug combo.

Most patients take tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. Tacrolimus is the backbone. Doctors aim for blood levels of 5-10 ng/mL in the first year, then lower it to 4-8 ng/mL. Too high, and you risk kidney damage or tremors. Too low, and your body rejects the liver.

Mycophenolate stops immune cells from multiplying. It’s tough on the stomach-30% of people get nausea or diarrhea. It can also lower your white blood cell count, making you more prone to infections.

Prednisone, a steroid, was once standard for everyone. But now, nearly half of U.S. transplant centers use steroid-sparing protocols. They drop prednisone after the first month. Why? Because steroids cause weight gain, diabetes, and bone loss. Cutting them out reduces diabetes risk from 28% to 17%.

Even with perfect adherence, rejection happens. About 15% of patients have an acute rejection episode in the first year. It’s often caught early through blood tests. Treatment usually means increasing tacrolimus or adding sirolimus.

Long-term side effects are serious. After five years, 35% of patients have kidney damage from tacrolimus. One in four develops diabetes. One in five has nerve problems like shaking or trouble sleeping. Mycophenolate adds more gastrointestinal issues and low blood counts. You’ll need regular blood tests, kidney checks, and diabetes screenings for the rest of your life.

Living Donor vs. Deceased Donor: What’s the Difference?

Choosing between living and deceased donor transplants isn’t just about timing-it’s about risk, access, and geography.Living donor transplants mean shorter waits. In high-MELD patients, the average wait for a deceased donor liver is 12 months. With a living donor, it’s about three months. But the donor must be healthy, aged 18-55, with a BMI under 30. Some centers are now considering donors up to BMI 32 or even 35, with close monitoring.

Deceased donor livers come from two sources: donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after circulatory death (DCD). DCD donors account for about 12% of transplants. Their livers are more fragile. They have higher rates of bile duct problems-25% versus 15% for DBD livers. But new technology is helping. Machine perfusion, a system that keeps the liver alive and oxygenated outside the body, reduces bile complications by nearly a third. The FDA approved the first portable perfusion device in 2023, extending preservation time from 12 to 24 hours.

Geography matters. If you live in California (OPTN Region 9), you might wait 18 months for a liver with a MELD of 25-30. In the Midwest (Region 2), the wait is only 8 months. That’s not a difference in medical need-it’s a difference in organ supply and policy.

What Happens After You Go Home?

Leaving the hospital is just the beginning. The first year is intense. You’ll have weekly blood tests for three months, then every two weeks for the next three months, then monthly. After a year, you’ll go in every three months. Each visit checks your liver function, kidney health, drug levels, and signs of infection.Medication costs are high. You’ll spend $25,000 to $30,000 a year on immunosuppressants alone-not including doctor visits, lab tests, or emergency care. Insurance coverage is a major hurdle. One in three transplant candidates has had coverage denied for pre-transplant evaluations.

You must be perfect with your meds. Missing even one dose increases rejection risk. You need to recognize the warning signs: fever over 100.4°F, yellow skin or eyes, dark urine, extreme fatigue, or swelling in your belly. Call your team immediately if you notice any of these.

Infection prevention is critical. Avoid raw fish, undercooked meat, and unpasteurized dairy. Wash your hands constantly. Stay away from crowded places during flu season. Get your flu shot and pneumonia vaccine every year.

Centers with dedicated transplant coordinators have 87% one-year survival rates. Those without? Only 82%. That’s why having a case manager who knows your history, tracks your labs, and answers your questions makes all the difference.

What’s Changing in Liver Transplantation?

The field is evolving fast. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), linked to obesity and diabetes, now causes 18% of transplants-up from just 3% in 2010. That number will keep rising.New guidelines are relaxing some rules. The AASLD plans to allow donors with controlled high blood pressure and BMI up to 32. Some centers are testing ways to wean patients off immunosuppression entirely. In pediatric cases, a therapy using regulatory T-cells has allowed 25% of children to stop all drugs by age five.

There’s also a push for equity. In British Columbia, Indigenous patients now get culturally tailored support during psychosocial evaluations. Abstinence requirements are being reviewed to reflect real-world recovery patterns, not rigid timelines.

But here’s the hard truth: no artificial liver device can replace a transplant yet. Even the most advanced machines only keep people alive for a few weeks. For now, a healthy donor liver is still the only cure.

Can you live a normal life after a liver transplant?

Yes, most people return to normal activities within six to twelve months. Many go back to work, travel, exercise, and even have children. But you’ll always need to take immunosuppressants, attend regular checkups, and avoid risky behaviors. Quality of life improves dramatically, but it’s not the same as having a healthy liver from birth.

How long do liver transplants last?

About 70% of transplanted livers are still working after five years. Many last 10-20 years or longer. Survival depends on how well you take your meds, avoid infections, and manage side effects like diabetes or kidney disease. Some patients need a second transplant if the first one fails.

Can you drink alcohol after a liver transplant?

No. Even if your original liver disease wasn’t caused by alcohol, drinking after transplant damages the new liver and increases rejection risk. Alcohol also interacts dangerously with immunosuppressants. Most centers require lifelong abstinence.

What if I can’t afford the medications?

Many transplant centers have financial counselors who help patients apply for patient assistance programs, Medicaid, or drug manufacturer discounts. Some nonprofits offer grants for transplant-related costs. Never stop your meds because you can’t pay-talk to your team. There are options.

Is it safe to be a living liver donor?

For healthy donors, the procedure is generally safe, but it’s major surgery. About 20-30% experience complications like bile leaks, infection, or pain. The risk of death is very low-around 0.2%. Donors are carefully screened for health, mental readiness, and long-term support. Recovery takes 6-8 weeks, and most return to full activity.

Can you get a liver transplant if you have cancer?

Only in specific cases. For hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), you must meet the Milan criteria: one tumor under 5 cm or up to three under 3 cm, with no spread to blood vessels. For cholangiocarcinoma, you need six months of tumor stability after treatment. Other cancers usually disqualify you unless they’re completely gone and have a very low risk of returning.

Why is there such a long wait for a liver transplant?

There aren’t enough donor livers. About 11,000 people are on the waiting list in the U.S., but only 8,000 transplants are done each year. Priority goes to the sickest patients (highest MELD scores), but geography affects access. Some regions have more donors than others, creating long waits in places like California.

What are the biggest risks after a liver transplant?

The biggest risks are rejection, infection, and side effects from immunosuppressants. In the first year, rejection is most common. Later, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers become bigger concerns. Sticking to your care plan reduces these risks significantly.

What You Need to Do Next

If you’re considering a liver transplant, start by talking to a hepatologist. They’ll refer you to a transplant center. The evaluation takes 3-6 months and includes heart tests, lung scans, mental health checks, and social work interviews. Don’t wait until you’re in crisis. The earlier you start, the better your chances of being ready when a liver becomes available.If you’re thinking about being a living donor, contact a transplant center directly. They’ll guide you through the screening process. It’s not a decision to make lightly-but for many recipients, it’s the gift of life.

Kiranjit Kaur

December 21, 2025 AT 12:22Just read this whole thing and honestly? Tears. 😭 My uncle got a liver transplant last year - living donor, his sister gave him part of hers. He’s back to coaching little league now. It’s not magic, but it’s damn close to it. Thank you for writing this so clearly.

Jim Brown

December 22, 2025 AT 09:58The profound ontological weight of organ transplantation lies not merely in its physiological mechanics, but in its radical reconfiguration of the boundary between self and other. The donor’s organ, once a part of another’s embodied existence, becomes the very substrate upon which the recipient’s identity is recursively reconstructed - a living testament to the fragility and generosity of human interdependence.

Sam Black

December 22, 2025 AT 14:02That bit about machine perfusion extending preservation time to 24 hours? Game-changer. I work in transplant logistics - we’ve seen a 40% drop in organ discard rates since adopting portable perfusion devices. Still, the disparity in wait times between regions is unethical. A guy in Nebraska with a MELD of 28 gets a liver in 6 weeks. Someone in LA waits 18. That’s not medicine. That’s lottery.

Jamison Kissh

December 23, 2025 AT 09:48If we’re talking about equity, why are we still using MELD scores as the sole metric? It doesn’t account for social determinants - housing, food access, transportation to appointments. A patient with a MELD of 30 who lives in a shelter and can’t afford bus fare to dialysis is just as likely to die post-transplant as someone with a MELD of 35 who has a support system. The system rewards survival potential, not just medical need.

Nader Bsyouni

December 23, 2025 AT 21:58So you’re telling me I can’t drink after a transplant but I can eat 3000 calories of fried chicken every day? That’s the real problem. Who decided alcohol is evil but sugar is fine? Also why do we still use steroids? Everyone knows prednisone turns you into a puffball. This whole system is outdated

Julie Chavassieux

December 25, 2025 AT 08:42My sister almost died waiting. We waited. Two years. She cried every night. The doctors said ‘be patient.’ But patience doesn’t grow livers. And now? She’s alive. But she’s scared. Every time she feels tired. Every time she gets a cold. Every time she sees a pill bottle. She’s not living. She’s surviving. And I’m still mad.

Tarun Sharma

December 26, 2025 AT 23:26Thank you for the comprehensive overview. The ethical considerations surrounding living donors and the strict sobriety requirements are deeply nuanced. This information will assist in guiding my patients with clarity and compassion.

Cara Hritz

December 27, 2025 AT 22:50wait so if you have cancer you can get a liver? i thought only if you had like cirrhosis?? also i think the mald score is called meld? i think i read that wrong

Candy Cotton

December 28, 2025 AT 09:14Why are we giving organs to people who drank themselves sick? We have veterans who served our country and need livers. Why is a guy who chose to binge drink for 20 years getting priority over a hardworking American who never touched a drop? This is not justice. This is rewarding bad choices.

Jeremy Hendriks

December 30, 2025 AT 04:40Let’s be real - the whole transplant system is a corporate circus. Insurance companies dictate who lives. Drug companies profit off lifelong immunosuppressants. Hospitals make millions. Meanwhile, donors risk death for a system that won’t even fix the waitlist. We need to nationalize organ distribution. Stop letting geography decide who dies. This isn’t healthcare. It’s capitalism with scalpels.