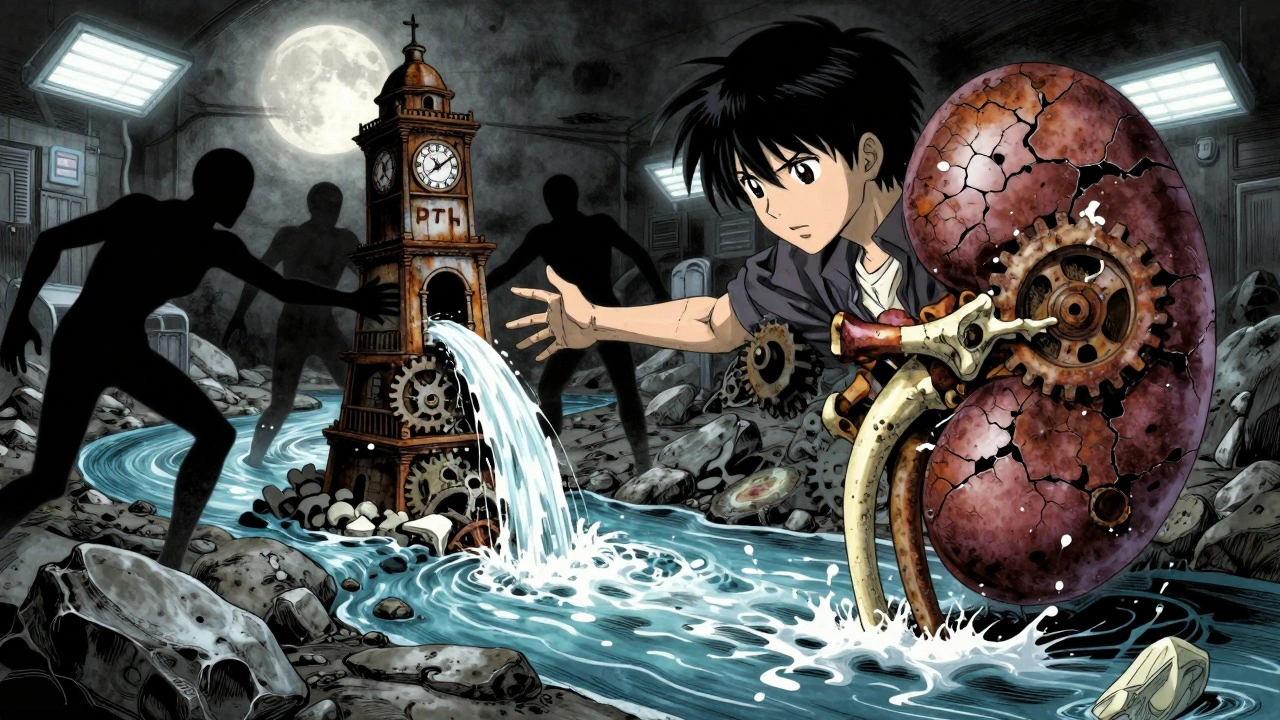

What Is CKD-Mineral and Bone Disorder?

When your kidneys start to fail, they don’t just stop filtering waste-they also lose their ability to keep your bones and blood chemistry in balance. This is called Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder, or CKD-MBD. It’s not just about weak bones. It’s a full-body problem involving calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), and vitamin D. By Stage 3 of kidney disease, nearly 90% of patients already show signs of this disorder. By the time someone needs dialysis, it’s almost universal.

For years, doctors called this condition "renal osteodystrophy," thinking it was just a bone disease. But now we know better. CKD-MBD affects your heart, your blood vessels, your muscles, and your bones-all at once. High phosphate levels cause calcium to deposit in your arteries. Low vitamin D makes your bones brittle. And your parathyroid glands go into overdrive trying to fix it, making things worse.

The Three Players: Calcium, PTH, and Vitamin D

Think of calcium, PTH, and vitamin D as a team that normally works together to keep your bones strong and your blood chemistry stable. In CKD, that team falls apart.

First, your kidneys can’t get rid of phosphorus anymore. As phosphorus builds up, it pulls calcium out of your bones and into your blood. That sounds good-until your blood calcium drops because your kidneys can’t activate vitamin D. Without enough active vitamin D (calcitriol), your gut stops absorbing calcium from food. Your blood calcium stays low.

Your body notices this and screams for help. The parathyroid glands, located in your neck, respond by pumping out more PTH. This hormone tries to pull calcium from your bones and increase calcium reabsorption in the kidneys. But in CKD, your bones stop responding properly. Even with high PTH levels, your bones don’t rebuild. This is called "PTH resistance." You end up with high PTH, low calcium, and weak bones-all at the same time.

Why Vitamin D Isn’t Just About Bones

Most people know vitamin D helps with bone health. But in CKD, it’s more than that. Your kidneys turn inactive vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D) into its active form, calcitriol. When kidney function drops below 60 mL/min, this conversion slows down-sometimes by 80%. That’s why 80-90% of people with Stage 3-5 CKD are vitamin D deficient.

Low vitamin D doesn’t just hurt your bones. It makes your parathyroid glands grow larger and more active, worsening PTH levels. It also weakens your immune system and increases inflammation. Studies show that people with vitamin D levels below 20 ng/mL have a 30% higher risk of dying from heart disease or infection.

Here’s the catch: giving you active vitamin D (like calcitriol or paricalcitol) can help lower PTH-but it also raises calcium and phosphorus. That’s dangerous if your vessels are already calcifying. That’s why doctors now start with regular vitamin D (cholecalciferol) first. It’s safer, cheaper, and lowers death risk by 15% without causing spikes in calcium or phosphorus.

PTH: The Body’s Cry for Help

Parathyroid hormone is your body’s emergency signal. When calcium drops or phosphorus rises, PTH jumps up to fix it. In early CKD, PTH levels above 65 pg/mL are common. By Stage 5, over 80% of patients have PTH levels above 300 pg/mL.

But here’s the twist: high PTH doesn’t always mean your bones are breaking down. In fact, many patients with very high PTH end up with "adynamic bone disease"-a condition where bone turnover is so low, your bones stop remodeling entirely. This happens because long-term high PTH, combined with uremic toxins, makes your bone cells stop responding. You can have normal bone density but still fracture easily.

Doctors don’t just look at PTH alone. They check bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BSAP) and PINP, markers of bone formation. If PTH is high but BSAP is low, your bones are shutting down. If both are high, you’re at risk for osteitis fibrosa cystica-a painful, bone-deforming condition.

What Happens to Your Bones and Blood Vessels?

CKD-MBD doesn’t just show up in blood tests. It shows up in your body.

Your bones become fragile. Dialysis patients have 4 to 5 times the risk of hip fractures compared to healthy people their age. Even if your DEXA scan looks normal, your bone structure is crumbling inside. You might not feel it until you fall-and then you break a bone that shouldn’t have broken.

At the same time, calcium and phosphorus start sticking to your arteries. Coronary artery calcification is present in 40% of Stage 3-4 CKD patients and over 80% of those on dialysis. This isn’t just plaque. It’s actual bone-like material forming inside your blood vessels. Each 1 mg/dL rise in serum phosphate increases your death risk by 18%. That’s why doctors call vascular calcification the "silent killer" of kidney disease.

One study found that dialysis patients lose bone strength at the same rate as postmenopausal women with osteoporosis-but they’re also losing heart function at the same time. It’s a double hit.

How Is It Diagnosed?

You won’t feel CKD-MBD until it’s advanced. That’s why blood tests are critical.

Every 3 to 6 months, your doctor should check:

- Serum calcium: Target 8.4-10.2 mg/dL

- Phosphate: Target 2.7-4.6 mg/dL (Stage 3-5), 3.5-5.5 mg/dL (on dialysis)

- PTH: Target 2-9 times the upper limit of normal for your lab (usually 150-600 pg/mL)

- 25-hydroxyvitamin D: Minimum 30 ng/mL

Bone biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing bone turnover-but it’s rarely done. Too invasive. Instead, doctors use PTH and BSAP together to guess what’s happening in your bones. If your PTH is low but you’re still breaking bones, you likely have adynamic bone disease. If PTH is sky-high and your bones hurt, you might have high turnover disease.

Vascular calcification is checked with a chest X-ray or a CT scan. The Agatston score measures how much calcium is in your coronary arteries. A score over 400 in a dialysis patient means you’re at very high risk for a heart attack.

How Is It Treated?

Treatment isn’t about fixing one number. It’s about balancing the whole system.

Phosphate control: The first line is diet. Limiting processed foods, colas, and dairy helps. Most patients need to eat under 800-1000 mg of phosphate daily. But it’s nearly impossible without binders. Phosphate binders stick to phosphate in your gut so it doesn’t get absorbed. Calcium-based binders (like calcium carbonate) are cheap-but they add more calcium to your system, which can worsen calcification. That’s why non-calcium binders like sevelamer or lanthanum are preferred. They cost more, but they’re safer for your heart.

Vitamin D: Start with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). Take 1000-4000 IU daily. Only move to active forms like calcitriol or paricalcitol if PTH is above 500 pg/mL and you’re not responding. Active forms can cause dangerous spikes in calcium and phosphorus.

Calcium: Keep it in the normal range. Don’t let it drop too low. But don’t push it too high. Calcium-based binders should never exceed 1500 mg of elemental calcium per day. Aluminum-based binders? Avoid them. They cause brain and bone toxicity.

Calcimimetics: If PTH stays above 800 pg/mL despite everything else, drugs like cinacalcet or etelcalcetide can help. They trick your parathyroid gland into thinking calcium is higher than it is, so it makes less PTH. Etelcalcetide, given by IV during dialysis, lowers PTH by 45%-better than cinacalcet’s 30%.

The New Thinking: Start Early

The biggest shift in CKD-MBD care? It starts way before dialysis.

FGF23, a hormone made by bone cells, rises as early as Stage 3 CKD-years before phosphate goes up. It’s the first warning sign. Klotho, the protein that helps FGF23 work, drops by 50-70% in early CKD. That’s why phosphate control now begins at Stage 3, not Stage 5.

Doctors are starting to test vitamin D and phosphate every 6-12 months in Stage 3 CKD. If FGF23 is high, they treat with vitamin D and dietary changes-not wait until PTH explodes.

In children with CKD, this early approach is life-changing. Without it, they grow poorly-often ending up 1.5 to 2 standard deviations below normal height. With early vitamin D and phosphate control, many catch up.

What’s on the Horizon?

Research is moving fast. Anti-sclerostin antibodies like romosozumab are being tested in CKD patients. In early trials, they increased bone density by 30-40%. That’s huge for people with adynamic bone disease.

Klotho replacement therapy is also in animal trials. Giving Klotho back to mice with CKD cut vascular calcification by 60%. Human trials are coming.

The message is clear: CKD-MBD isn’t a bone disease. It’s a whole-body syndrome. You can’t fix one part without looking at the others. Treat phosphate, vitamin D, and PTH together. Start early. Monitor regularly. And remember-your bones and your heart are connected.

What You Can Do Today

- Ask your doctor for your last phosphate, calcium, PTH, and vitamin D levels.

- Review your diet with a renal dietitian. Cut out processed foods, colas, and added phosphates.

- If you’re on a phosphate binder, make sure it’s not calcium-based unless absolutely necessary.

- Take vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) daily-unless your doctor says otherwise.

- Don’t ignore bone pain or fractures. They’re not just "old age."

CKD-MBD is complex. But it’s not hopeless. With the right care, you can protect your bones, your heart, and your future.

Makenzie Keely

December 3, 2025 AT 09:31Joykrishna Banerjee

December 4, 2025 AT 17:12Myson Jones

December 5, 2025 AT 13:59parth pandya

December 5, 2025 AT 16:32Albert Essel

December 6, 2025 AT 01:40Charles Moore

December 6, 2025 AT 09:41Gavin Boyne

December 6, 2025 AT 11:49Rashi Taliyan

December 8, 2025 AT 00:07Kara Bysterbusch

December 8, 2025 AT 14:03Rashmin Patel

December 10, 2025 AT 10:23sagar bhute

December 11, 2025 AT 11:51Cindy Lopez

December 12, 2025 AT 02:46James Kerr

December 12, 2025 AT 03:39